Theoritical and Empirical studies on generalization in Deep learning

Theory: Bound the generalization error

Introduction

Probably approximately correct (PAC) learning (Valient, 1984) provided a theoretical framework to provide a uniform convergence bound on the generalization error (the difference between training error, denoted as \(\hat{e}(h)\), and the true error, denoted as \(e(h)\), for the whole data population, test error is used to approximate this error) for a machine learning model given the model complexity (\(|H|\)) and the sample complexity (The number of trainingd data, N).

The PAC criterion is that the model has low generalization error \(\epsilon\) with high probability \(\delta\):

\[P(|e(h) - \hat{e}(h)| \leq \epsilon) \geq 1 - \delta\]By untilizing the Hoeffding bounds, we can find for finite hypothesis agnostic case (the hypothesis space may not contain the true hypothesis, that is the modeling function we choose cannot model the real relationship)

\[P(e(h) < \hat{e}(h) + \epsilon) \leq \|H\|e^{-2N \epsilon^2}) \leq \delta\] \[N \geq \frac{1}{2 \epsilon^2}(ln(\|H\|) + \ln{(1/ \delta)})\]and for infinite hypothesis agnostic case, \(N = O(\frac{1}{\epsilon^2}[VC(|H|)+\ln(1/ \delta)])\) ref

Basically, the generalization error could be written as

\[e(h) \leq \hat{e}(h) + O(\frac{some \ function\ of \ the \ model\ complexity}{\sqrt{N}})\]This theory has been used to estimate the number of training data needed for machine learning algorithm

Applied to deep learning

Earlier studies (Mitchell, 1997) used PAC to estimate the number of iid samples needed for a feedforward neural network given a desired generalization error. A recent study (Du & Wang et al, 2019) gives a tigher bound for fully connected neural network, convolutional network and recurrent network with one-hidden layer using input/hidden feature size (and input sequence length for RNN).

However, this approach would fail for many modern deep learning network structures because the networks are overparameterized. The Lottery Ticket Hypothesis (Frankle & Carbin, 2018) suggests that there exists a subnetwork can perform equally well as the large network if we can properly choose the intialization weight (In this case, they need to use the same initialization value used in the full network to train the subnetwork). In other words, to really understand the generalization of deep learning models, we cannot simply use some function of the number of parameters in the network to represent the model complexity, and apply PAC, instead, we need to think about how the optimization methods (SGD and its varients) and the underlying data distribution restrict the deep networks to “simpler” models. (think about the subnetwork.)

Many methods has been proposed for a refined version of the uniform convergence bound for deep learning. (That is, some function of the model complexity in the nominator changes to a more elaborte function that may also consider data distribution, training optimizer, etc). Despite all the efforts, recently, Nagarajan & Kolter showed that uniform convergence bound may not be able to fully explain the generalization in deep learning and we need to think of other ways to derive the generalization bounds for deep networks.

Theory: Estimate the expected generalization error

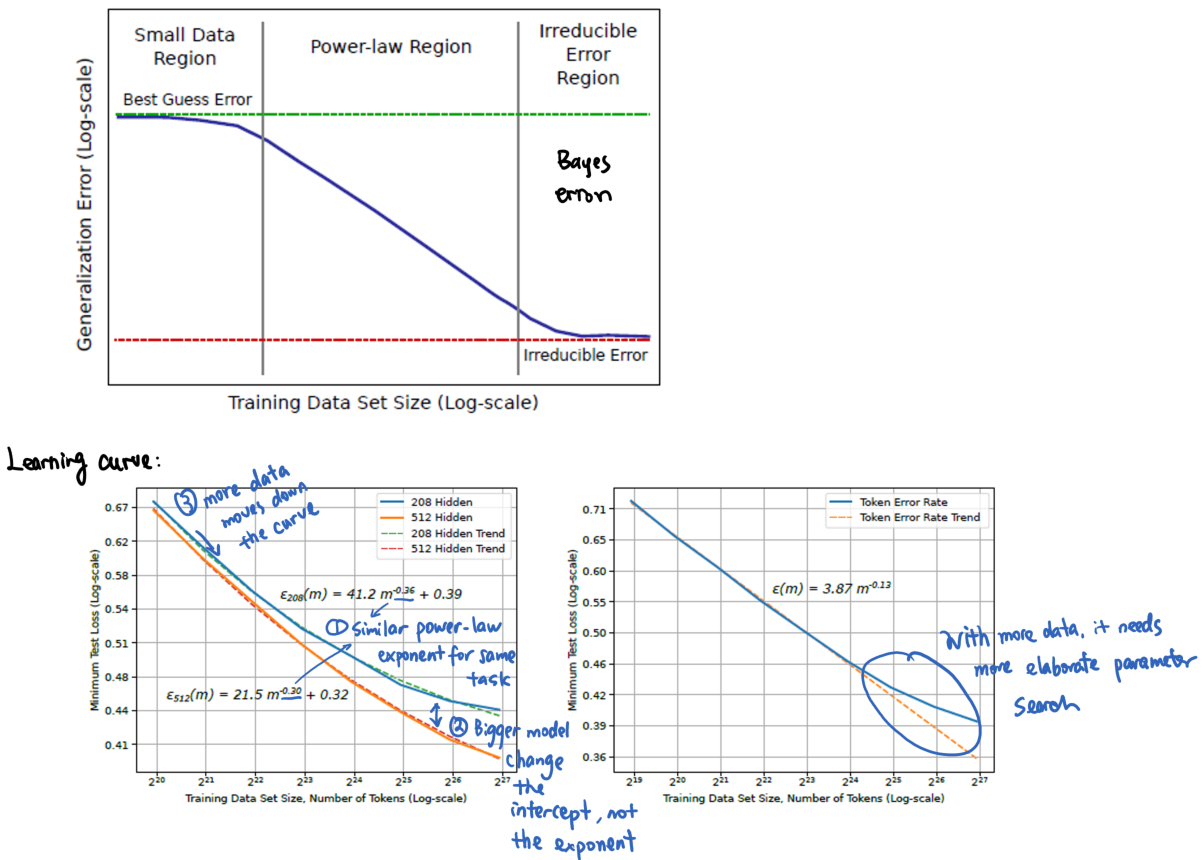

It has been shown that when the expectation is calculated over all possible data distributions, as sample complexity increases, generalization error will decline following a power-law

\[e(N) \sim \alpha N^\beta\]with \(\beta=-0.5,-1,-2\). This power-law rule was observed in some empirical studies. However, it could not explain many choices of \(\beta\) in real applications.(Hestness et al, 2017) (The writer thinks this is because the theoritical bound is calculated given all possible distribution, but the experiments are conducted on different datasets one by one)

Experiments: relationship between loss and the number of training data

In practice, one could plot the learning curve (number of training data vs. training and validation loss) to see if the model has enough training data. If the differences are huge (it is overfitting), add more data or add regularization.

To provide a more general guideline for the number of training data needed for deep learning, Hestness et al did experiments on several popular deep learning tasks (word-based language model, character-based language model, image processing and speech recognition.) and found that:

- Power-law generalization error scaling is observed across a breadth of factors (tasks, model size, model type, and optimizer).

- Similar power-law exponents \(\beta\) for the same task.

- Model improvements only shift the error but do not appear to affect the power-law exponent.

- However, the result is yet to be explained by theoretical work.

- They also show that model size scales sublinearly with data size.(See figure b for all figures in their paper)

- So they suggest to search the model structures with a small training data (as long as it is in the power-law zone), and do a finer parameter sweep with large dataset to save time.

Conclusion

There are still no concrete conclusion on the number of parameters needed for a network. New theoritical tools need to be invented. However, there are several empirical guidelines we can refer.

References

Valiant, L. G. (1984). A theory of the learnable. Communications of the ACM, 27(11), 1134-1142.

Du, S. S., Wang, Y., Zhai, X., Balakrishnan, S., Salakhutdinov, R. R., & Singh, A. (2018). How many samples are needed to estimate a convolutional neural network?. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 373-383).

Mitchell, T. (1997). Computational Learning Theory. In Machine learning (pp. 201–229). Burr Ridge, IL: McGraw Hill.

Frankle, J., & Carbin, M. (2018). The lottery ticket hypothesis: Finding sparse, trainable neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.03635.

Nagarajan, V., & Kolter, J. Z. (2019). Uniform convergence may be unable to explain generalization in deep learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 11611-11622).

Hestness, J., Narang, S., Ardalani, N., Diamos, G., Jun, H., Kianinejad, H., … & Zhou, Y. (2017). Deep learning scaling is predictable, empirically. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.00409.